Can rural African communities address human-wildlife conflict in the face of climate change?

Human-wildlife conflict is a perennial problem in southern Africa, where Indigenous people and local communities live alongside dangerous wild animals such as elephants, lions, spotted hyaenas, buffaloes and hippos. Crop damages and livestock losses due to these and other species are common occurrences in community conservation areas, while damage to infrastructure (e.g., water reservoirs, housing) is less common but often more costly. Tragically, scores of people are injured or killed by wild animals every year in the region.

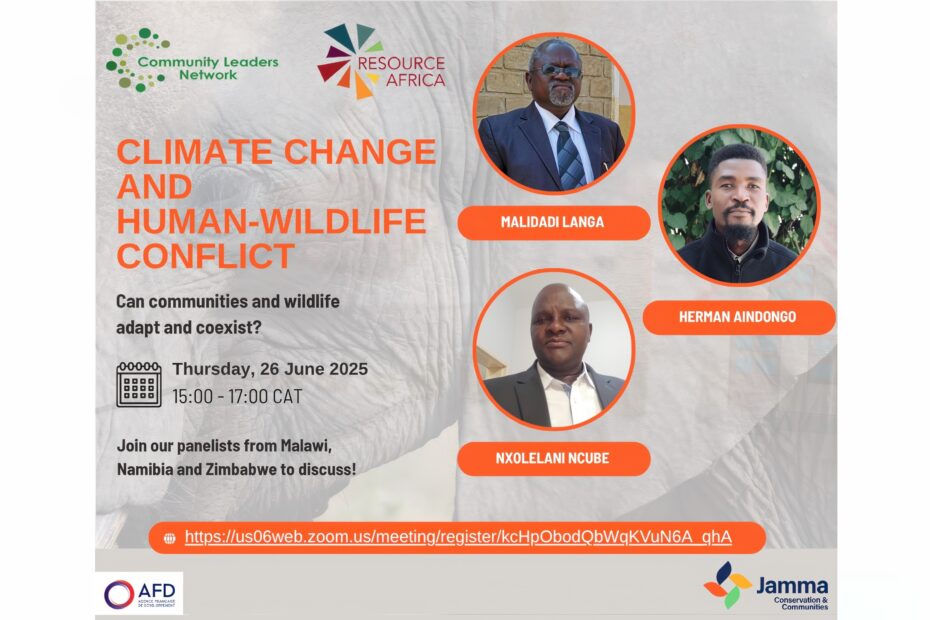

The climate predictions for southern Africa suggest that most areas will get hotter and drier in future. This means that droughts will be more frequent and severe in many areas. In this webinar jointly hosted by Community Leaders Network of Southern Africa and Resource Africa, the speakers showed that drought often led to increased human-wildlife conflict. As water and food resources become scarce during a drought, animals start approaching human settlements to meet their needs. It is therefore likely that climate change will exacerbate human-wildlife conflict across southern Africa in the future.

Herman Aindongo from Namibia, Malidadi Langa from Malawi, and Nxolelani Ncube from Zimbabwe presented on their experiences of conflict and, where available, showed data on conflict incidents over time. Mr Aindongo, representing the Namibian Association of CBNRM Support Organisations (NACSO), used the national data from Namibian communal conservancies. While the kinds of human-wildlife conflict vary across the country, with livestock losses predominant in the drier regions and crop damages in the wetter regions, the data from this country show spikes in conflict during drought years.

Around Malawi’s Kasungu National Park, the recent spike in human-elephant conflict is directly related to the translocation of elephants into the park. Mr Langa from Kasungu Wildlife Conservation and Community Development Association (KAWICCODA) nonetheless warned that conflict would increase if conflicting land uses continue to be promoted around the park – for example, tobacco farming is actively promoted on the lands around Kasungu. The lack of land for food production, along with farming practices that damage soil health, drives people into the park. Holistic land use planning must be prioritised to address these issues, especially as climate change is expected to further reduce agricultural productivity.

One strange trend Mr Langa noted was the increase in human attacks by spotted hyaenas, which is unusual behaviour for this species. Further research is required to find out what is causing hyaenas to attack people in order to address this issue.

Mr Ncube from Hwange Rural District Council in Zimbabwe noted that human-elephant conflict is most common in the communities living around Hwange National Park in CAMPFIRE (Communal Areas Management Programme for Indigenous Resources) areas. Hwange is home to 45-55,000 elephants, and this large population comes under severe stress during drought years. Besides the elephants, lions, spotted hyaenas, crocodiles and hippos become more dangerous to people, crops and livestock during droughts. Snaring is another factor that can increase conflict, as shown in one incident where an elephant lost its trunk due to a snare and then killed cattle that approached it.

It was clear from all three countries that human-wildlife conflict is related to numerous factors, one of which is drought. In the discussions that followed, moderated by Dr Shylock Muyengwa, audience members from different countries in southern Africa were encouraged to share their own experiences and thoughts. The difficulties experienced in Malawi, Namibia and Zimbabwe are similar to those found in other countries across the Southern African Development Community (SADC). SADC has yet to develop a common policy on addressing human-wildlife conflict, which may help to reduce the frequency of conflict and its socio-economic impact on rural communities.

Compensation is one way to reduce the economic impacts of human-wildlife conflict. It is currently being implemented in some southern African countries, but not others. This is one area where SADC countries can learn from each other’s experiences and develop a transboundary policy that all countries can apply. Since the wildlife in the region regularly crosses international boundaries, more needs to be done to harmonise policies associated with wildlife in SADC.

Addressing conflicting land uses between conservation, agriculture and mining, is one way that African countries can reduce human-wildlife conflict. As agriculture and mining takes up increasing amounts of land near or within national parks, wildlife is pushed into smaller areas and connectivity between parks (especially critical during droughts) is reduced. Under such conditions, conflict is inevitable and will be further exacerbated by climate change.

A number of technical solutions have been tested in the region and were noted by the presenters and audience. Chili fences around crop fields and chili bombs (chili mixed with elephant dung that is lit to produce smoke) have proven to be useful for deterring elephants from entering crop fields. Strong predator-proof bomas reduce livestock losses to predators that tend to attack livestock at night. In some landscapes, elephants and lions are fitted with satellite collars that enable early warning systems, whereby communities are alerted to the danger and can take steps to protect themselves when these animals enter their lands.

The community-based organisations in Namibia and Zimbabwe that earn income from hunting and tourism have helped to implement some of these solutions alongside their respective governments and non-government partners. In Malawi, Resource Africa has worked with communities around Kasungu National Park to improve their agricultural practices, which increases household income and reduces their need to enter the park.

Community-based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM), which allows communities to derive income from the sustainable use of wildlife, is a key enabling condition for addressing human-wildlife conflict. It is likely that CBNRM will become even more important in the face of climate change, as it can help reduce land use conflicts, implement technical solutions to conflict, and create an important channel for conservation finance aimed at conserving species that are involved in conflict.

In his concluding remarks, Dr Muyengwa noted the need for multi-stakeholder and multi-sectoral approaches, particularly at the regional SADC level. As a regional body representing communities in SADC, CLN is well placed to take up these concerns at this scale. National CLN members should look to work with multiple sectors—not just the conservation authorities—within their countries to address this complex issue in a holistic manner.

To watch the full webinar, click here. Passcode: xnG1i%Ps