A Southern African view on the UN Decade on Restoration

By Resource Africa

Natural ecosystems support life on earth, whether one lives in a city or on a farm. People living in rural areas are more connected with this fact than others in urban areas, however. Soil, water, and wild foods (including plant products, meat and fish) provide sustenance and a source of income for indigenous peoples and local communities living in rural areas.

Ecosystem services are not an abstract idea for these communities, but the source of life. These ecosystems are under threat worldwide and poor rural communities, such as those in Africa, suffer the consequences of such degradation. In southern Africa, woodlands, savannahs and aquatic ecosystems are threatened by deforestation, excessive use of water resources, rangeland mismanagement and over-fishing, which are further exacerbated by climate change and pollution.

Since rural communities stand the most to lose due to ecosystem degradation, they have a vested interest in restoration initiatives. Yet these key local stakeholders are too often overlooked due to the global nature of the threat and the need for international action. In this second article in our series on the recently published Community-based Conservation Horizon Scan, we look at the issue of ecosystem restoration and how communities can use this global agenda to drive positive local change.

The United Nations (UN) Decade on Restoration provides an opportunity for communities to get involved in or be recognised for either protecting or restoring ecosystems. The UN General Assembly proclaimed this Decade, 2021-2030, on the 1 st of March 2019. The UN links its effort to restore ecosystems with achieving all 17 of the Sustainable Development Goals that have also been set for 2030.

Rural communities in southern Africa that are engaged in Community-based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM) have already been contributing to protecting and restoring woodlands, savannahs and aquatic ecosystems. Communities should therefore take the opportunity presented by the UN Decade on Restoration to generate support and funding for their efforts. Here, we look at some of the community-based restoration projects in southern Africa for each of these ecosystems.

1. Protecting and restoring woodlands

Miombo woodlands cover close to 2.7 million km2 in southern Africa. Image courtesy of CWMAC Tanzania.

Preventing deforestation overlaps with the goal of mitigating climate change, as woodlands and forests are a major carbon sink. The Lower Zambezi and Luangwa Community Forests projects in Zambia, supported by the BioCarbon Project, are excellent examples of what can be done. These projects combine reducing carbon emissions, protecting ecosystems and providing tangible benefits for the communities involved.

Measuring the emissions saved through protecting woodlands and selling these emissions on carbon markets require technical expertise, thus creating a barrier for more communities across southern Africa to generate benefits from reduced deforestation and degradation. The UN’s Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) framework is designed for implementation at the national level, which could lead to top-down implementation that ignores the needs or potential contributions of local communities.

While communities cannot start to implement REDD+ projects and reap the benefits without government support and technical assistance, they can however prepare for such initiatives by establishing Community Forests or similar institutions. Given the social and environmental safeguards required within the REDD+ framework, the presence of Community Forests can make a particular area more attractive for external investors or technical partners who need legitimate local partners for implementation.

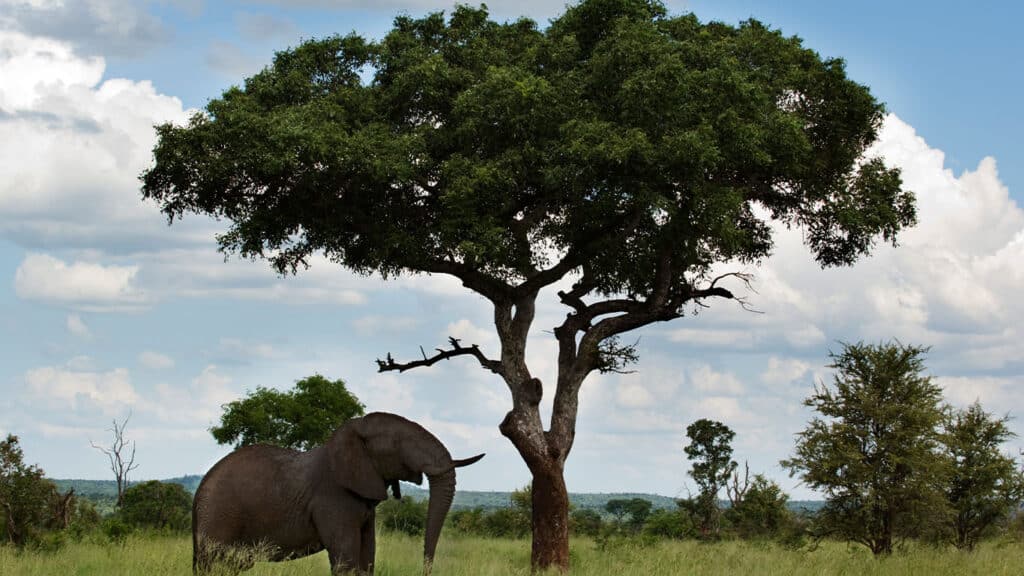

2. Protecting and restoring savannahs

Savannahs cover about half of the African continent, supporting humans, livestock and large mammals like the savannah elephant.

While savannah ecosystems have less potential for generating income from carbon credit schemes than forests, they play a major role in supporting rural livelihoods. Most of southern Africa is covered by savannah – a mix of grassland and woodland – that is used primarily as grazing lands for livestock. The savannah also supports a large diversity of wild herbivores that in turn support carnivore species.

Maintaining a savannah ecosystem thus fits better with biodiversity conservation than climate change mitigation efforts, although these overlap. The opportunities for communities involve livestock husbandry practices that reduce rangeland degradation, improve livestock health and reproduction, and reduce vulnerability to predation. A southern African model for this is the Herding 4 Health project in South Africa and Botswana that aims to achieve these multiple benefits through more intensive livestock herding following locally adapted grazing plans.

This programme is again a partnership between non-governmental organisations with expertise and local communities. In this programme, Eco-Rangers selected by their communities play a critical role in managing the cattle based on their own knowledge and training they receive on rangeland management. Building strengthened cattle enclosures that can protect cattle from lions and other predators is another key aspect for communities living near protected areas.

Following the example set by the climate change offset schemes, southern African communities and support NGOs are starting to experiment with Payment for Ecosystem Services schemes that rewards communities based on the presence of threatened wild animals or the conservation of wildlife corridors. A Namibian version called Wildlife Credits pays communities for protecting wildlife corridors and high value species, while the Community Camera Trapping project in Tanzania rewards communities based on the document presence of wildlife on their land.

Expanding and sustaining these initiatives will require long-term funding. If communities and their partners can show that their efforts have multiple benefits to the savannah ecosystem, this could open the door for increased funding as part of the global ecosystem restoration agenda.

3. Protecting and restoring aquatic ecosystems

Coastal communities in Mozambique, which has 2700 km of coastline, rely heavily on marine resources for food security and livelihoods.

Fishing communities along rivers and coastlines in southern Africa are stepping up to restore their respective freshwater and marine ecosystems, especially the fish stocks they rely on for survival. Over-fishing, especially for commercial purposes, is a major threat to Africa’s rivers and marine ecosystems. While community conservation efforts have previously focused on terrestrial ecosystems, the same principles of governance and sustainable use can be applied to aquatic ecosystems.

In both systems, communities identify and protect no fishing zones in parts of the river or coastal area where fish breed. The increased abundance of fish in these zones spills over to the fishing grounds used by the community, who also implement rules around the type of fishing gear that can be used. Particularly fine nets, for example, catch very small fish before they have a chance to mature and breed, thus reducing population growth.

Namibia’s Community Fisheries Reserves and Mozambique’s Community Fishers’ Councils (Conselhos Comunitarios de Pesca) are examples of how this works in freshwater (Namibia) and marine (Mozambique) ecosystems. The best performing fisheries reserves or sanctuaries are those where the community recognised the need to save their fish and created the impetus for the project. As with the woodland and savannah projects, however, technical support from NGOs and enabling government policies are required for communities to fully achieve their conservation goals.

Most Southern Africa countries have been implementing CBNRM for many years as a means of linking rural development with nature conservation through government-recognised community-based organisations. This enables rural communities to claim rights and responsibilities to use and manage their natural resources. Research shows that when rights are upheld and incentives for conservation are provided to those who live alongside and manage such natural resources, there are positive conservation outcomes benefiting people and nature.

Conclusion: Partnerships for Ecosystem Restoration

The ecosystems discussed here cover vast areas in southern Africa and beyond. Many of these initiatives are still small and all of them require some level of external support. One of the major challenges facing the UN Decade of Restoration is that ecosystem protection and restoration efforts need to happen on a massive scale and relatively quickly before ecosystems are degraded or lost.

Success hinges on whether a particular local community owns and drives the initiative, whether government policies and national plans provide an enabling environment, and if the necessary technical expertise and funding is available from NGOs, donors or the private sector. Achieving all three of these prerequisites in many areas across multiple countries in a short time frame will simply not be possible without collaboration across national borders. As we have seen with the examples in this article, many of the countries in southern Africa have programmes that protect one or more of these key ecosystems. This provides an opportunity for the communities, national governments and support organisations to learn from one another to either start new programmes or improve existing ones. The Community Leaders Network of Southern Africa (CLN), supported by Resource Africa and Jamma International, is an ideal platform for the communities to share lessons learned. At government level, the Southern African Development Community (SADC) provides another platform. At a continental scale, the African Civil Society Organisations’ Biodiversity Alliance (ACBA) brings together NGOs working on the continent. Finally, the inaugural African Protected and Conserved Areas (APAC) Congress held in Kigali, Rwanda marks an important step towards bringing all three of these groups together to share their work and discuss their challenges. We believe that a pan-African network arising from this Congress would have enormous potential to mobilise resources in a way that increases both the scale and effectiveness of ecosystem protection and restoration in Africa.